GIP’s rise and the decline of industrial sponsors

How did GIP go from start-up in 2006 to a $12.5 billion price tag 17 years later?

Of the global project finance heads who bestrode the market 25 years ago Adebayo Ogunlesi has undoubtedly emerged as the most successful. The $12.5 billion sale to BlackRock of Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP), which Ogunlesi founded in 2006, leaves him with a fortune estimated at $2.3 billion. Billion-dollar fortunes based on infrastructure development are not unusual – particularly in emerging markets – but those based purely on infrastructure finance are more rare.

There will be plenty to say about why BlackRock made a tilt for GIP, and what the acquisition means for the various managers inside both GIP and BlackRock as the merger beds down. Ogunlesi has already stressed that the acquisition will be complementary, suggesting – perhaps slightly uncharitably – that BlackRock’s equity investment skills were more focused on the mid-cap sector, compared to GIP’s blockbuster deals, and that GIP’s debt offerings are more focused on lower-rated credits than BlackRock’s investment grade platform, which is a little more fair.

But the bigger question is probably how Ogunlesi, Jonathan Bram, Matt Harris and Michael McGhee timed the launch of their infrastructure investment venture so well, and what made it so successful. Ogunlesi has been typically self-effacing when discussing the launch of GIP, saying that it chose to focus on infrastructure because it was less crowded than mainstream private equity, though the markets have since converged, with heavyweights KKR, Blackstone and Carlyle all now sporting decent-sized infrastructure offerings.

It is perhaps better to say that in 2006 infrastructure investment was generally seen as an outgrowth of the businesses that had emerged in Canada and Australia serving those countries’ institutional investors’ real assets allocations. Macquarie was already a big player in infrastructure, though its record in managing listed funds had been patchy. IFM, Ontario Teachers and OMERS all had established infrastructure investment businesses.

GIP was not the first global infrastructure fund to be founded by a former project finance global head. That honour goes to Alinda Capital, since renamed Astatine Investment Partners, which Citi’s former global head of project finance, Chris Beale, founded in 2005. But Beale joined straight from that role, taking the opportunity to move to the equity side as Citi drastically scaled back its lending activities in project finance.

Ogunlesi had further to progress at CSFB before founding GIP, switching from global head of energy to global head of investment banking at CSFB, and chief client officer from 2004 to 2006. As head of investment banking at CSFB, he led one of the bank’s periodic brutal restructurings, and was not the first leader to struggle to control CSFB’s piratical urges.

CSFB – indeed Ogunlesi – had pioneered the use of third party debt capital in project finance, whether from project funds, debt funds or leveraged loans. Ogunlesi left CSFB on good terms, attracting $500 million in initial backing from Credit Suisse, along with a similar amount from General Electric.

At the time, the most obvious opportunities for a fund with this pedigree were in the US, where a gradual recovery in power markets post-Enron suggested that consolidation was on the cards in the independent power sector, and where two years before GIP’s founding Cintra and Macquarie had turned heads by acquiring the Chicago Skyway.

Instead, GIP made its name acquiring European airports – most notably London City and Gatwick – where Ogunlesi points to incremental improvements to the passenger experience as the reason for GIP’s success. Perhaps equally important was GIP’s insistence on expanding its assets’ access to the bond market. It was one of the airport operators that aggressively adapted the whole business securitisation structure pioneered in UK water to aviation assets.

This access to institutional debt capital undoubtedly made GIP more resilient to the 2008 financial crisis than many of its peers, and also prompted it to move into credit products, closing on the $739 million GIP Capital Solutions Fund I in 2014. It’s now commonplace to think of the large global generalist infrastructure fund managers playing across infrastructure assets’ capital structure, but much more rare, outside distressed situations, ten years ago.

This move to disintermediate the banks was a long time coming – the first alarm bells about banks’ ability to fund long-dated infrastructure debt commitments rang with a first indication that the Basel II capital adequacy proposals would be fairly punitive for banks in 2000. And banks are still the major players in providing debt capital for greenfield development – short-dated deals for vanilla assets.

But GIP’s rise was in large part a function of the withdrawal, or at least shrinking, of the equity providers that had dominated infrastructure before its launch. In power these were the large, usually US, utilities that had expanded into unregulated generation, but which were retreating from the market by 2006. In infrastructure, these were the French Spanish, German and UK construction contractors that provided the initial capital for the PPP boom from the late 1990s up to the 2008 crisis.

Airports were simply the earliest opportunities for financial sponsors to take the lead in acquiring and upgrading brownfield assets. GIP’s funds now also invest in three leading US independent power producers – Clearway Energy, Competitive Power Ventures and Terra-Gen. As these players evolve as the portfolios of financial sponsors, the bank relationships that underpin that growth become more transactional, as the cross-selling opportunities that bound industrial/strategic sponsors to their banks become more scarce.

The Proximo perspective

GIP is part of the movement that first reduced the competitiveness of industrial sponsors as buyers of brownfield assets, leaving them to return to making most of their returns (or losses) from construction work, and then increasingly saw financial sponsors as the most obvious providers of equity capital for project development.

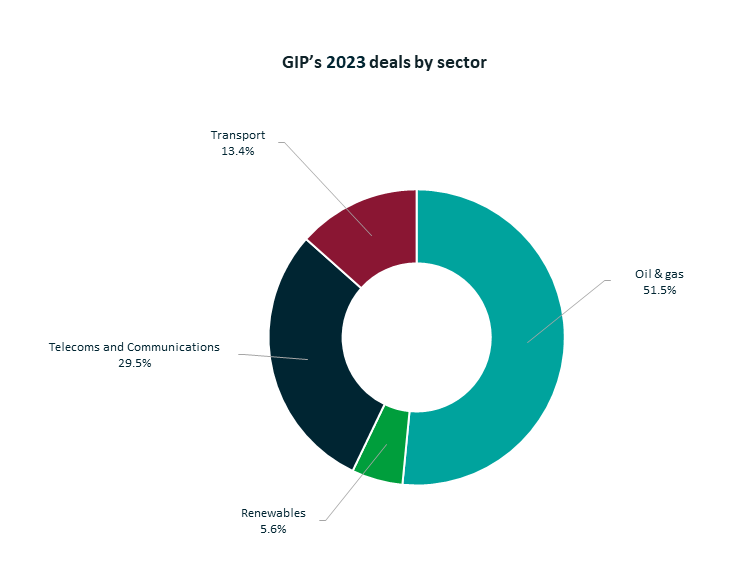

Two recent GIP financings – for the Galaxy ADNOC pipeline acquisition in the UAE and the Rio Grande LNG greenfield development – demonstrate both approaches at scale, though both are not without their ESG concerns. GIP has also moved aggressively into the digital infrastructure space, making investments in tower, cable and data centre assets.

GIP has not shied away from the carbon-intensive end of the infrastructure market, and BlackRock, which has led the move to embed ESG processes, may look to rein back that level of exposure to hydrocarbons. But with oil & gas the destination for big equity cheques and the source of quick and handsome returns, that clash, rather than managerial egos, could be the most testing aspect of the merger’s aftermath.