Nigerian solar: The path to bankability

There have been notable recent developments in the Nigerian regulatory and legal framework aimed at promoting investment in solar independent power projects (IPPs). But key bankability issues remain, which many argue have been the cause of limited development of Nigeria’s solar industry and power sector as a whole.

At the recent One Planet Summit, the African Development Bank’s president Akinwumi Adesina stated that renewable energy, particularly solar power, is the key to driving economic development in Africa and combating climate change. And given Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation (around 200 million) and largest economy, it has caught the attention of the global solar industry.

According to Power Africa (the USAID-funded energy initiative), around 95 million Nigerians have no access to electricity. This unmet demand, combined with Nigeria having one of the highest levels of solar irradiance in West Africa, makes the country an attractive proposition for local and international solar investment.

This has been further cemented by the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) implementing a range of policy initiatives to promote the development of renewable energy IPPs.

In 2016, the national electricity offtaker, Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Company, signed power purchase agreements (PPAs) with a number of developers for the development, construction, financing and operation of 14 solar IPPs with a combined capacity of 1,200 MW (the 14 Solar IPPs).

In 2018, Nigeria’s Rural Electrification Agency, together with the African Development Bank (AfDB), also announced a 1,000 MW rural solar energy electrification program to be implemented in the city of Gwiwa, Jigawa State, in northern Nigeria. And in January 2019, Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Education, as part of a wider policy decision to develop 2,000 MW of renewable power for all federal universities, issued a tender for what could be Africa’s first international project-financed solar IPP with an integrated energy storage system.

However, despite the FGN’s efforts to promote investment in renewable IPPs, and ostensible investor appetite for the sector, projects have not progressed as quickly as many expected – to date, none of the 14 Solar IPPs have achieved financial close.

Notable initiatives and developments

The FGN aims to generate 30GW of installed on-grid electricity capacity by 2030, of which 30% is to be generated by renewable energy sources. In 2015, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) published feed-in-tariffs for use of renewable energy sources (REFIT), which provide:

• a minimum guaranteed price per unit of electricity generated by renewable IPPs;

• an obligation on NBET to purchase all electricity supplied by renewable IPPs within the capacity limit defined in REFIT programme; and

• a standardised allowance for interconnection costs.

In 2017, the FGN, in consultation with the World Bank, released the ‘Power Sector Recovery and Implementation Plan’ (PSRIP). The PSRIP is a comprehensive programme of policy, legal, regulatory, operational and financial interventions aimed at restoring the viability of Nigeria’s power sector in the long-term. The measures, which are to be implemented by 2021, are aimed at improving transparency and re-establishing investor confidence, with the objective of achieving greater investment within the Nigerian power sector.

The World Bank Group partial risk guarantee (PRG), MIGA termination guarantees and certain other guarantees from multilaterals have sometimes been available for projects in the Nigerian power sector. For example, as part of the privatization of the electricity generation assets in Nigeria, under the National Integrated Power Policy (NIPP), the Calabar 560 MW power plant benefited from a $120 million World Bank PRG in relation to the project’s gas supply agreement. The Azura IPP (as defined below) also benefited from the World Bank PRG as well as MIGA political risk insurance. It remains, however, uncertain whether such multilateral support and guarantees will be extended to renewable projects in Nigeria.

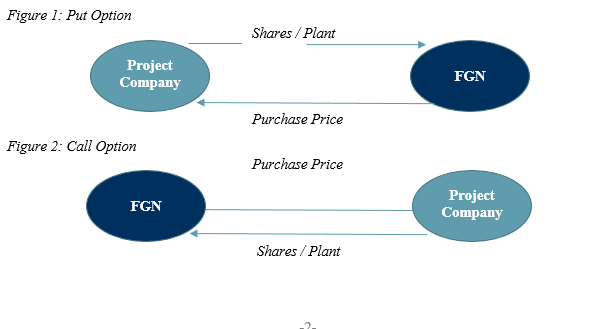

Put and call option agreement

Following the financial close of the Azura-Edo IPP – a 461MW open-cycle gas turbine power station in Edo State and the first international project-financed IPP in Nigeria – in December 2015, many believed that the overall risk allocation agreed in the project would serve as a model that could be ‘cut and pasted’ for a string of IPPs financed by international investors in Nigeria.

A critical element of the agreed risk allocation in the Azura IPP was the put and call option agreement (PCOA). Under the terms of the Azura IPP PCOA, the project company (or its sponsors), have the right to require that the FGN purchases the IPP (or the shares in the project company) in the event of early termination of the PPA (the Put Option). The PCOA also provides the FGN with the right to require the project company (or its sponsors) to transfer the IPP to the FGN or its designee in specified circumstances (the Call Option).

In either case, the FGN will be required to pay a purchase price for the IPP or the sponsors’ shares -such purchase price will be determined in accordance with one of a number of different formulae set out in the PCOA, depending on the event that led to the early termination. Under the terms of the Azura IPP PCOA, regardless of the cause of the termination of the PPA, the purchase price would always cover the senior debt outstanding to the lenders whilst equity may be recovered in full, partially or not at all depending on the cause of the termination.

The FGN does not provide sovereign guarantees in respect of NBET’s payment obligations under PPAs. Therefore, the PCOA is the closest protection that a developer will receive from the FGN to a government guarantee.

As mentioned above, many stakeholders assumed that the Azura IPP PCOA would establish a precedent for future IPPs. However, the FGN decided to alter the risk allocation established in the Azura PCOA and proposed a new form of PCOA which in turn raised concerns for lenders and developers.

One of the main issues under the then proposed PCOA was that it no longer included the Put Option present in the Azura IPP. Furthermore, the proposed purchase price was changed from US dollars to Naira, Nigeria’s local currency, which exposed developers and lenders to large foreign exchange risk.

However, following prolonged negotiations between project developers, international lenders and the FGN, the FGN have conceded some of the key issues as set out above and an updated PCOA was issued by the FGN in 2017. Two projects out of the 14 Solar IPPs have now accepted and executed the updated PCOA whilst discussions are ongoing with the other solar IPP developers.

Liquidity crisis

Under the terms of the standard NBET PPA, NBET undertakes to purchase electricity generated by the IPP for a term of 20 years for onward sale to distribution companies (Discos) who then supply the electricity to the consumers. Whilst IPPs are also permitted to execute PPAs with Discos directly, NBET was introduced to act as a credit buffer between IPPs and Discos. NBET’s credit worthiness and ability to fund its commitments under the PPA is supported by: (a) a $350 million Eurobond financing; (b) a $325 million government fund; (c) yearly capital commitments from the FGN of approximately $145 million; and (d) approximately $150 million of monthly receivables from Discos.

However, significant aggregate technical, commercial and collection (ATC&C) losses in the Nigerian power sector has led to a sector-wide liquidity crunch. The ATC&C loss can be described as the variance between the value of electricity received by a Disco from the transmission network and the amount of electricity for which it invoices its customers. Such loses arise as a result of a combination of technical, commercial and collection factors such as:

• outdated transmission and distribution infrastructure;

• an inaccurate customer database;

• unmetered customers;

• incorrect tariff classification of customers; and

• revenue collection inefficiencies.

It has been estimated that up to 46% of what should be earned from electricity sales in Nigeria is lost because of ATC&C losses, preventing Discos from upgrading their critical infrastructure, including metering systems. This, in turn, has affected the ability of Discos to collect payments efficiently, and, consequently has had an adverse effect on revenue and cash flow.

Whilst NBET is obligated to provide some form of payment security by way of a standby letter of credit issued by a commercial bank (meeting certain specified criteria) the market wide-wide liquidity crisis has left lenders and developers with little comfort on NBET’s ability to meet its payment obligations under the terms of the PPAs.

To address this issue, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has established a $1.8 billion facility – known as the CBN Nigerian Electricity Market Stabilisation Facility (NEMSF) – which serves as payment security for electricity supplied by the IPPs to NBET. It is expected NBET will draw on the NEMSF on a monthly basis, to meet its payment obligations to the IPPs.

It is hoped that the CBN’s intervention, coupled with other government initiatives, will help to alleviate the liquidity crises faced by the Nigerian power sector and in turn boost developer and lender confidence to invest in Nigerian solar IPPs and other renewable projects.

Electricity tariffs

NERC is the governmental authority charged with ensuring that the electricity tariffs for power supplied by Discos to consumers allows each Disco to recover the full costs of their business activities and to make a reasonable return on capital. To aid this, NERC issues Discos a Multi-Year Tariff Order (MYTO) which is subject to periodic review.

Contrary to investor expectation, as well as the framework established by applicable law and rules (such as the REFIT programme), none of the MYTOs issued by NERC have established a stable and cost-reflective pricing structure. This is largely due to the political risks involved in increasing the cost of electricity for end-users and the substantial difference between the projected and assumed inputs of the tariffs (inflation, available generation capacity, foreign exchange rate fluctuation, etc.), and the actual figures of each of those inputs.

The MYTO methodology sets the electricity tariff based on certain key assumptions and variables (which are required to be reviewed every six months by the NERC), including:

• the national rate of inflation;

• exchange rate fluctuations;

• the increase in the price of natural gas; and

• capital expenditure requirements for the entire electricity sector.

Unfortunately, the current electricity tariff does not take into account changes in the macroeconomic factors listed above. For example, the assumption of an exchange rate of the Naira to the US dollar calculated at the official CBN exchange rate plus a 1% premium, is no longer a reasonable assumption given the recent devaluation of the Naira and fluctuation of the foreign exchange rate.

The effect of such non-cost-reflective tariffs has been exacerbated by the liquidity crunch and until NERC implements a tariff model which allows Discos to recover their costs and make a reasonable profit, the government may be continually forced to introduce measures as set out above to pump liquidity into the power sector, rather than the sector developing a self-sustaining model which is fair and equitable for all parties.

Conclusion

For the reasons highlighted above, Nigeria presents a real opportunity for local and international investment in the development of solar IPPs and the wider renewable energy sector. However, to convert this opportunity into bankable projects, the FGN will need to continue to address the liquidity crisis as well as introduce cost reflective tariffs that will encourage and facilitate local and international investment. It is hoped that the PSRIP will achieve its aims of re-establishing investor confidence and, in turn, greater investment within the Nigerian power sector.

Authors details:

Oliver Irwin

Partner

T +44.(0).207.448.4228

F +44.(0).207.657.3124

oliver.irwin@bracewell.co

Oliver Irwin regularly advises both sponsors and lenders on the development and financing of cross-border power projects and has extensive project financing experience in Africa. IFLR1000 has ranked Oliver every year since 2013 and identifies him as “Highly Regarded” and he has been ranked in Chambers and Partners each year since 2012, where clients report that Oliver is considered "truly outstanding" and highlight his "knowledge of debt financing" and "drive to get the deal done".

Ade Mosuro

Associate

T +971.4.350.6865

F +971.4.350.6801

ade.mosuro@bracewell.com

Ade Mosuro is a projects lawyer based in our Dubai office. Ade focuses on project development and project finance transactions throughout Africa and the Middle East. He has represented sponsors, lenders and contractors active in the power sector. Ade is a dual Nigerian and British national with first-hand experience and a deep understanding of the African market, as well as the unique challenges associated with different types of projects in various jurisdictions across Africa.